One potential solution is hydrogen, an energy source that emits no carbon dioxide during use. But high production costs have long been an obstacle to its widespread adoption. Now a new venture underway in Australia hopes to cut the cost, using a plentiful resource that was mostly considered worthless until now: brown coal.

Tim Howard is a 33-year-old coal miner who lives an hour-and-a-half south of Sydney. The mining industry is a regional fixture and has long provided stable employment opportunities for the people of the area, including Howard and his father. But now, the global movement away from carbon has stoked worries about the future.

Tim Howard and his father have been working in the mining industry but Tim is wondering if his offspring can continue the tradition.

"It is a concern with the way that environmental concerns are progressing that the coal mining industry won't be around, perhaps not to the end of my career," Howard says. He adds that if he had a son, he would not want him to work in the industry.

Coal mining has long provided stable employment opportunities for people in some areas of Australia.

But a low-carbon future may not be entirely hopeless for Australia's coal miners. The country has vast deposits of lignite, or "brown coal". Easily combustible, brown coal is considered unfit for export and has been used only for local thermal power plants. Japanese companies have come up with a way to extract hydrogen from it, producing what they hope could be a low-cost fuel of the future.

A consortium of firms has launched a project in the Australian state of Victoria, with backing from both countries' governments.

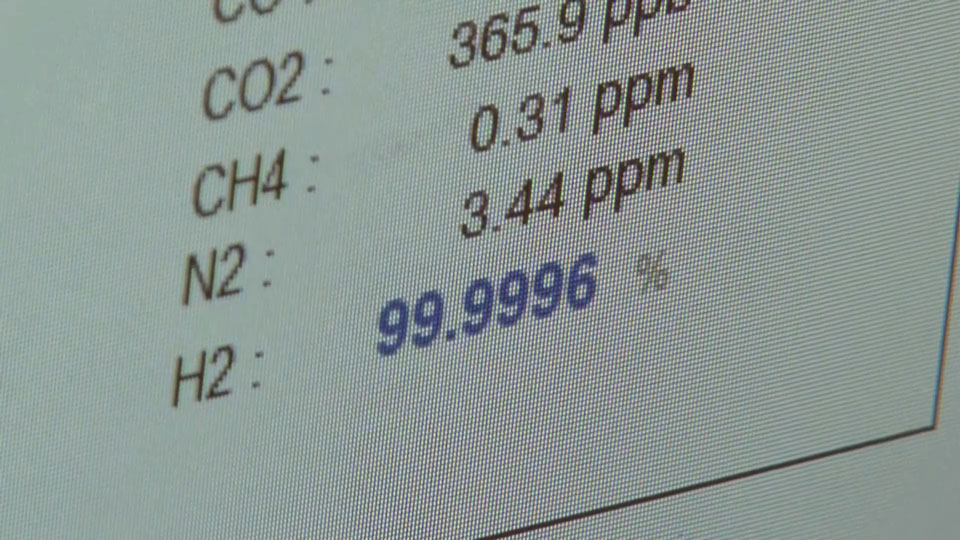

The process begins with the heating of brown coal. This triggers the release of several gases, including hydrogen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. The hydrogen is then separated from the other gases and purified for use. It took several months for Japanese engineers to find a way to effectively purify the hydrogen.

When brown coal is heated, it releases several gases including hydrogen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. The hydrogen is then separated from other gases to be purified for use.

But producing hydrogen was just the first challenge. They also have to transport it. For this, the hydrogen needs to be liquefied and kept at minus 253°C. Due to its extremely low liquefaction temperature, it has never been shipped overseas before.

The solution: the world's first liquefied hydrogen carrier, built by Japanese manufacturer Kawasaki Heavy Industries. It is equipped with a tank that has an insulated double-shell structure to prevent temperature fluctuations during transport. It is scheduled to make its first delivery to Japan by early next year.

The world's first liquefied hydrogen carrier, built by Japanese manufacturer Kawasaki Heavy Industries, is scheduled to make a landmark delivery to Japan by early next year.

Kawazoe Hirofumi, the General Manager of Hydrogen Engineering Australia, a subsidiary of Kawasaki Heavy Industries, believes there is great potential for hydrogen in Australia.

Kawazoe Hirofumi, General Manager of Hydrogen Engineering Australia

"We will do everything we can to ensure that in the future people can use hydrogen as a main energy source for their electricity usage," he says. "After the pilot phase is completed, we will review the results and start planning for a massive commercial phase."

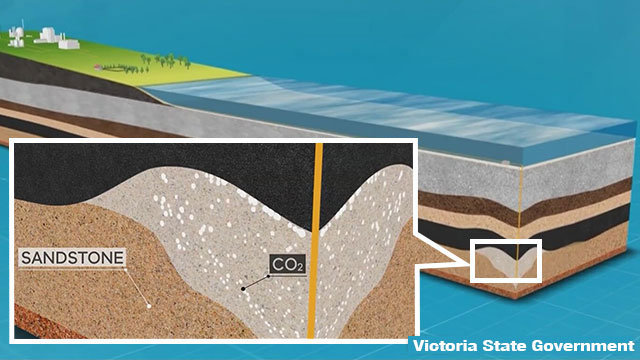

But one question remains: what to do with the carbon dioxide released during hydrogen production. The Victorian state government is leading efforts to develop technology to capture CO2 emissions and store them under the ocean floor. Researchers believe the seabed off the coast of Victoria, which has a sponge-like layer of rock, would be suitable for capturing CO2, with a solid bedrock above to seal it in.

The seabed off the coast of Victoria has a sponge-like layer of rock, perfectly suited for capturing CO2, and a solid bedrock above that seals it in.

The Victorian government expects the pilot project to create 400 jobs. Once it advances to the commercial phase, there could be thousands more.

"Being able to find a useful and environmentally sensitive use of that resource hopefully will give wealth and opportunity to the community," says state treasurer Tim Pallas.

If the project is a success and leads to wider production of hydrogen in Australia, hydrogen could become one of the country's main exports. That could also help Japan take a big step towards its goal of a 46-percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 2013 levels.

Source: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/1698/